For approximately the last 20 years, Eastern Band Cherokee Indian elder Jerry Wolfe, 93, has been working as a volunteer at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian greeting tourists and other visitors at the ticket counter with a “Siyo” meaning “Hello.”

In an effort to preserve his traditions, Wolfe openly shares his Cherokee heritage to anyone through storytelling at the museum.

Growing up in Big Cove in the 1930s and 1940s was a challenge for Wolfe as his family was very poor. There were no paved roads or running water in their home. Wolfe had to make do with the hand he was dealt.

Getting up early in the morning to help his family with chores and having to walk everywhere on trails was a typical thing for Wolfe.

“We had to walk. Of course, we learned a lot just by walking through the mountains because we spotted things as we walked along the trails,” said Wolfe.

In school, Wolfe’s fellow Cherokee had a difficult time because, in order to do the work assigned, they had to first grasp the English language.

“We lived far away from the schools. We had a hard time with the language because all us Cherokee Indian kids, we didn’t know any English at all…A lot of kids didn’t make it out of the first grade, the first year, because they had to learn the English,” said Wolfe.

Wolfe had an advantage that a lot of his fellow Cherokee didn’t. His mother was his first English language teacher at home.

“I learned English from home because my mother finished up through the fifth grade, and she spoke English well. In fact, they even offered her a teaching job if she wanted to teach,” said Wolfe.

In addition to learning English, his parents dropped him off at the Cherokee Boarding School when he was only seven-years old. The students had to march and salute the flag everyday which taught him the value of hard work and perseverance. If a student messed up in the march or didn’t salute the flag at any point, you get lashings as a punishment.

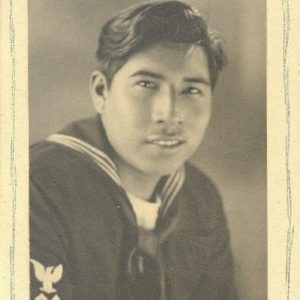

Young Jerry Wolfe serving in the U.S Navy during WWII. Photo courtesy of Cherokee One Feather.

Although he didn’t know any better at first, speaking in Cherokee was forbidden by the boarding school. It was this strict nature that ultimately aided him as he arrived for the navy’s basic training before heading to WWII. He was sent to several places across the country to train, including Indianapolis and Virginia, until he was shipped out across the Atlantic into Europe.

“As they gave the commands that first morning, the old chief jumped up on a table giving orders and he looked around and pointed his finger right at me,” said Wolfe.

Wolfe had thought he had done something wrong, but the chief wanted to know if he had been in the military before. The chief was intrigued that Wolfe already knew the commands because of his military structure at the Cherokee Boarding School.

Since Wolfe already knew how to march, the chief gave him a platoon for him to teach the commands. He never had to give commands to anyone in his life, but he was up for the challenge.

Wolfe got to see and experience both the war in the Pacific and the Atlantic, surviving some close calls in the process.

“We returned back to England and we stayed there until midnight on the 5th of June. At that time we went on into the beach, and we were really, really fired on. I don’t know how we got by it. Just one of our guys was hit. It’s a wonder we weren’t cut into,” remembered Wolfe on his mission to Normandy across the English Channel.

Also, he witnessed the signing of the Japanese surrender documents to officially end the war in the Pacific on Sept. 2, 1945.

The segment shown above is of Jerry Wolfe storytelling live from The Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Dec. 9, 2016. Courtesy of Visit Cherokee’s Facebook page.

In his community, Wolfe has been a fixture since he was a young man as his desire to help others began as an adolescent. At about twelve-years old in the late 1930s, Wolfe became involved with what is now known as the Cherokee Boys Club, and assisted in growing a summer garden to aid the families in the region by selling vegetables such as potatoes. The club is still around today and provides on-the-job training to Cherokee children.

Wolfe’s dedication to serving his community through his stone masonry across the Smoky Mountains, as well as preserving Cherokee traditions, led the Tribal Council to name him the EBCI’s “Beloved Man” in 2013. If one should ask him about if he deserves the recognition, he would be humble about the distinguished honor.

Eastern Band Cherokee newspaper, One Feather, reported on the ceremony and quoted tribal representative Bo Taylor who submitted the resolution for naming Wolfe the “Beloved Man” in 2013.

“I think our old ways are so important,” said Big Cove Rep. Bo Taylor who originally submitted the resolution (the resolution was amended to state it was submitted by Tribal Council as a whole to show their unanimous support). “We talk about some really important issues. We talk about gaming. We talk about buying other land, but one thing that we need to remember is that the reason we sit here is because we are Indian people. We haven’t had this in a long time. It’s been many, many years since we’ve honored our elders in this way.”

Prior to Wolfe, the last recorded “Beloved Man” was Little Turkey in 1801. The “Beloved Man” or woman represents the Cherokee as an individual who is self-sacrificing and who is willing to do whatever to help his or her community.

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is a sovereign nation with more than 15,000 members and is the only federally recognized Native American tribe in North Carolina. The EBCI makes its home on the 56,600-acre Qualla Boundary in five Western North Carolina counties.

Related links: