Mountain organizations are raising awareness for an issue that plagues nearly every North Carolina community, yet often goes ignored.

An open discussion in Asheville, entitled “WNC Food Deserts & Food Policy,” centered around the concept of “food deserts,” and how a growing tally of Tarheel families, particularly rural ones, are finding themselves isolated from a much-needed meal.

Manna Food Bank volunteer Elisabeth McGuirk, of Asheville, prepares boxes of food donations for distribution on Jan. 29. Photo courtesy of Carolina Public Press.

“We may think that hunger couldn’t happen to us,” said Hannah Randall, Chief Executive Officer of Asheville’s Manna Food Bank. “But the reality is that the majority of us are only one or two bad situations away from being in a similar situation (as the underfed).”

The Feb. 17 event at Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Asheville campus was the first of ten sessions scheduled for Carolina Public Press‘ 2017 Newsmakers Series. Now in its third year, Newsmakers convenes panels of experts to discuss hot-button topics gripping the state’s western-most region.

In addition to Randall, the panel brought together Kiera Bulan, Director of the Asheville Buncombe Food Policy Council; Charlie Jackson, Executive Director of the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project; and Laura Sexton, registered dietitian for UNC-Asheville’s Chartwells dining service.

A food desert is recognized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as “parts of the country vapid of fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthful whole foods, usually found in impoverished areas.” It implicates a lack of easily-accessible food as the root problem, citing the absence of grocery stores, community farmer’s markets and “healthy food providers.”

“I can appreciate the analogy of the desert…,” said Charlie Jackson, head of one of the region’s top advocates for local farmers. “But a food desert is not just the absence of food. There’s implications associated with that. Economic implications, racial implications.”

A panel of hunger and agricultural experts speak about food deserts on Feb. 17 during the first Carolina Public Press Newsmakers event of 2017. Photo by Caleb Peek

The evidence is overwhelmingly in Jackson’s corner. A 2016 N.C. Justice Center study found that of the 50 states, only seven are hungrier than North Carolina. Sixteen percent of residents statewide, roughly 630,000 households, combat constant food insecurity. Just over 17 percent of North Carolinians live in poverty, another study reports.

Perhaps the most sobering data comes from the N.C. Association of Feeding America Food Banks, which finds that 25 percent of Tarheel children – one out of every four– aren’t guaranteed a daily meal. Randall says that in some rural pockets, four out of five children live in poverty.

“Food insecurity and poverty are undoubtedly correlated,” Randall said. “Without a doubt, I feel that we as a society have to address that issue. It doesn’t matter where you come from, we don’t want any child to go hungry.”

The first solution involves putting the hungry on a diet.

The panel suggested that community support of area food banks, such as Manna, is crucial to ensuring that low-income families have the nourishment they desperately need. But although Manna has plans to add a ‘food pod’ capable of housing an additional 30,000 pounds of food per year, according to Randall, their main concern is not so much quantity, but quality.

“Manna has dramatically increased distribution of fresh produce from 10 percent two years ago, up to 30 percent in 2016,” Randall said. “But unique challenges are present with fresh produce, especially regarding shelf life.”

In 2016, while managing the fallout following the passage of HB2, North Carolina passed a Small Food Retailer statute which provided funds for small grocery and convenience stores to stock healthier food options for customers. The requested funding was $1 million – the program was awarded a quarter of that amount.

But while food banks race the clock to put fresh produce on dinner tables, farmer’s markets have quietly become a solid source for crisp, field-to-consumer fruits and vegetables, as well as information on healthy living. Charlie Jackson says that even though the farmer’s market isn’t yet a primary nutritional source, the focus of nonprofits is shifting toward sustainable, healthy foods rather than a meal from a can.

“Less than one-third consume our daily allowance of fruits and vegetables,” Jackson said. “So it’s not only a poverty issue. We have a lot of farmer’s markets in western North Carolina, and they’re growing and I’m glad they’re visible, but they’re not a significant part of the food economy just yet. Right now, the focus is on reinforcing community and nutritional values.”

In addition to farmer’s markets, Jackson says that an increase in farm purchases in western North Carolina shows that the mountains, and elsewhere, are once again growing their own food.

“What’s happened is a national and global transition,” Jackson said. “People are connecting with food again, and understanding the impact that it has.”

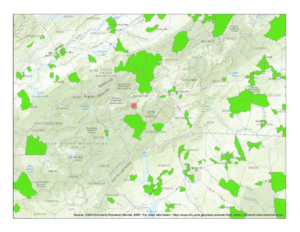

This USDA map of western North Carolina highlights the counties most affected by food depravity. Areas in green represent food deserts, which sometimes cover the majority of a county. Image courtesy of USDA.

An emerging concern for poverty-aid organizations is the lack of food accessibility in some areas, both rural and urban. A USDA map shows that food deserts can sometimes occupy the majority of a county; Graham, Lenoir and Swain counties are, per capita, the hungriest in the region.

In poverty-stricken areas, a family may live miles from the nearest grocery store with no vehicle to reach it. Children often get only one full meal per day, usually through a school lunch or a summer program. That’s why the YMCA-sponsored Mobile Food Bank is gaining traction among low-income communities.

The program, considered by YMCA to be an “outreach” effort, sends mobile food trucks into hungry locations and allows people to choose the foods that best suit their individual needs. It’s a take-what-you-need system, and it’s all free.

“We’re able to put out tons of food farmer’s market style,” Randall said, acknowledging that the partnership between Manna Food Bank, Mission Health and the Y is good for food stamp referrals as well as food and health education.

Manna Western Outreach Coordinator Jennifer Trippe thinks that sending out food trucks is a solid start. But she says that the organization and others like it can dig further into the root of hunger by learning the communities they serve.

“It’s important that folks working in our rural communities understand the community that they’re working in,” said Trippe, who oversees Manna operations in the state’s western-most counties. “Because they’re all different. Graham County is different from Jackson, and Macon is different from Clay. They sit right beside each other, but they’re all different.”

To fight a life-threatening situation for a growing number of North Carolina citizens, the panel said that citizens must get involved. While government agencies are lobbied to increase funding for hunger-alleviation programs, Randall says that each person can make a difference in his or her own way.

“I say give, volunteer, advocate and vote,” said Randall. “We all bring something to the table, and when we have all of our voices together, it can be incredibly powerful.”

See the full recording of the forum here.