Photo of Shelley Booth with her family in Western Sahara refugee camps, February 2016. Photo provided by Booth.

Meet Shelley Booth. She is 40-something Asheville mom, business co-owner, outdoor enthusiast and an activist. On Feb. 27 she ran her first marathon…. in the Sahara Desert. And she ran with a mission to help raise awareness and funds for the displaced Sahrawi people. She reached her goal and raised over $5,000 that will help rebuild the camp that was destroyed in October 2015 in the rain floods.

Booth’s connection to Western Sahara and the Sahrawi people started 20 years ago when she was a student at the university of Maryland and she met Zahra.

“Twenty years ago my anthropology professor told me to come to a presentation on Western Sahrawi,” said Booth, talking to a small group of students and faculty on March 15 to speak about Western Sahara and the refugees.

Booth currently lives in Asheville, NC. Booth and her husband own a business called Suspension Experts and she is known as the “voice of reason” in the shop. She focuses on managing the administrative side of the business. At one point, she even managed a childhood obesity prevention program.

In addition, in the past she worked in Baltimore, where Catholic Relief Services is based at helping international work in Albania, Serbia, and Liberia. She has worked in war zones and the refugee camps in areas like Western Sahara.

Western Sahara is a disputed territory in North Africa, bordered by Morocco to the north, Algeria to the northwest, Mauritania to the east and south, the Atlantic Ocean to the west. It was once known as Spanish Sahara, a colony of Spain in northwest Africa. In 1975, when they were about to get their independence from Spain, the territory was invaded by Morocco. Refugees of the Western Sahara had to flee into the Sahara Desert and have been there since. The camp that was built in 1975 is still there. It is not just camp – it is a state. In 1976 they have established a new government in exile called the Saharan Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The SADR is now recognized by over 80 UN countries worldwide.

One of the refugee camps tents. Photo provided by Booth

On the presentation at University of Maryland she met Zahra who told Booth when they first fled into the desert and created the camps that they had two priorities: adult literacy and universal education for the children. Because the men had to fight or go find means to support their families, women were left to organize all the aspects of camp life. The women even became elected officials in the camp’s government. Booth was shocked to hear about this because she heard that there was ambassadors there and jobs in the refugee camps – especially for the women. What Zahra said broke all stereotypes Booth had about refugees in general. Zahra was not a powerless victim.

Booth was “blown away” and told Zahra she would be there in the summer. Zahra just laughed, but eight months later in 1993, Booth was living in the camps with a refugee family and teaching an English class for three months.

“Commitment to education is so extensive [to them],” explained Booth, during the lecture she gave at WCU.

The education there is all about how to create to preserve the Sahrawi identity and culture. They have bilingual education, using Arabic and Spanish. Countries like Algeria, Cuba, Spain and even Qatar are giving scholarships to these students to go abroad and study. Sahrawi people are all about promoting autonomy.

“[It] amazes me this sort of thing is happening, but we don’t hear anything about it,” said Booth, referring to Western Sahara and the refugee community.

Since 1993 Booth has stayed in contact with her friends and she visits the camps whenever she can. It became an important aspect of her life. The people and the place are a part of her, she wrote in an email message.

Although the camp changed and in same way modernized in the past 40 years it is still a camp and a hard life for its inhabitants. The hot weather is brutal, and water is delivered in bladder tanks. When she was there in 1993 there was only one refrigerator in the camp, now they have TV and cell towers and she gets text messages from her friend Selma saying, “We are living in hard conditions and don’t know how our lives will be in the future.”

In the story Booth wrote for the Blue Ridge Outdoors she explained the political situation.

“Morocco and Western Sahara’s independence movement, the Polisario, fought a war for 16 years, then agreed to a UN brokered peace plan in 1991. The two sides agreed to a ceasefire and to hold a referendum — a vote for the Western Saharans to choose between integration with Morocco or independence. They have never been able to hold this vote. In all the years of stagnation, the hundreds of thousands of Saharawi refugees continue to live in the camps — forgotten and ignored for forty years. However, Morocco still maintains an illegal occupation in Western Sahara and controls the majority of the territory and its natural resources. In addition, Morocco built an earthen berm through the entire country, similar to a wall and second in length only to the Great Wall of China, to seal off the Western Saharan territory. The United States and France helped fund construction of the wall. Littered with an estimated 7-9 million landmines and costing Morocco $1 million a day to maintain, the wall prevents Western Saharans under Moroccan control from leaving and the refugees from returning home.”

Booth thinks that if the referendum happens Saharawis will vote for independence and Morocco does not want that to happen.

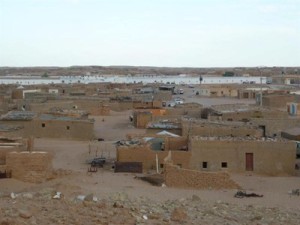

Sahrawi refugee camp. Photo provided by Booth.

“The UN Secretary General visited the camps last month and called for support of the referendum. Morocco’s response was to criticize the Secretary General and expel the UN staff from the occupied territory of Western Sahara. So you can see how they operate. The Saharawis will stay in the camps until they get to vote. A possible scenario is that the war could start again. Long answer, but the solution just isn’t clear,” said Booth in an email message.

With no solution in sight, Booth ran the marathon trying to help as much as she could. It was a symbolic attempt to mark the 40 anniversary of the camps and 16th marathon that raises awareness to the issue.

“The organizers have been having this event for 16 years and the biggest piece of it is to raise awareness and provide people first-hand real experience and build solidarity with the refugees,” said Booth.

These give opportunities for people to raise awareness, help rebuild structures and give money to children’s programs in sports, arts and music.

“There will always be people who are displaced from somewhere, and even when the dispute over Western Sahara is resolved, there will still be Syrians, Haitians, South Sudanese, Hondurans, and many more. It is our obligation as members of a powerful society to learn about these issues and take action however we can, whether it’s by volunteering or by voting. Shelley Booth’s experiences with the Saharawi can only help us to become a little more compassionate and a little more aware of the decisions that we make that can affect people on the other side of the planet,” explained WCU Spanish professor Lori Oxford who organized Booth’s visit to WCU.

Booth wants to advocate for their cause and raise awareness locally, eventually expanding it to the whole country.